An early form of needle lace: 12th century parchment repairs in the Engelberg monastery, Switzerland

While writing the medieval section of the Bloomsbury World Encyclopedia of Embroidery, vol. 4, Scandinavian and Western European Embroidery, I came across an article by Christine Sciacca (2010), ‘Stitches, sutures, and seams: “Embroidered” parchment repairs in medieval manuscripts’, in: (eds) Robin Nethertong and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Vol. 6, Woodbridge: the Boydell Press, pp. 57- 92.

In her study, Sciacca refers to mended manuscripts associated with the Engelberg monastery, a Benedictine foundation in central Switzerland. Among the items in the Engelberg Stiftsbibliothekare a number of medieval manuscripts made out of parchment sheets (animal skins from goats or sheep). Before being used the skins have to be prepared and repaired. It is the technique of preparing and repairing the sheets for the Engelberg codices that drew my attention.

Two parchment codices in particular caught my eye, namely, Augustinus: Sermones ad populum diversi (Cod. 16), and Gregorius M: Moralia in Job, t. III (Cod. 22). The sheets in these two codices, both of which dated to between AD 1147 and 1178, include numerous slits, gaps and holes, some of which are natural, others accidentally made during the preparation process (when scraping the skin, etc.).

A mended slit using simple stitching that has been pulled so tight that in the process more holes were created (Engelberg, Stiftsbibliothek / Cod. 22 – Gregorius M., Moralia in Job, t. III / f. 36r).

A number of these defects were mended, sometimes with stitching, before the sheets could be used. Based on the stitching quality, this was done with varying levels of skills! The repairers appear to have used silk and possibly linen threads for the process.

It is the way in which the stitching was worked that proved to be most intriguing and hints at the early use of what is commonly known as needle lace and until now generally dated to the sixteenth century and later.

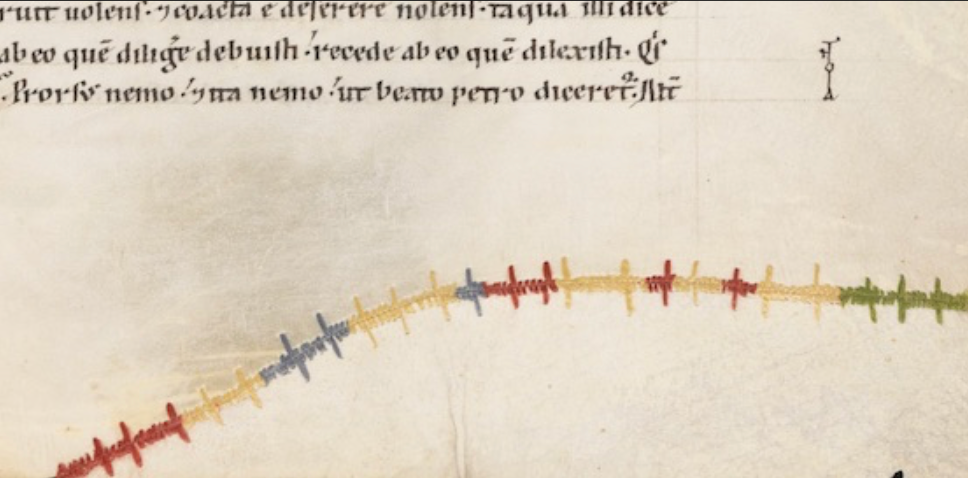

Many of the repairs are made using joining plait stitch in order to combine two pieces of parchment. The simplest form is in one colour with stitches of an even length on both sides of the seam. The more complicated forms have a saw-tooth effect in silk of one or more colours.

One point I want to observe here refers to the bright colours of some of the repairs. It would appear that there was no inclination to ‘hide’ the repairs, as many would now do. Quite the reverse! Perhaps it was a case of another modern concern, namely sustainability – during the medieval period coloured silk threads were expensive and left overs from making liturgical vestments, etc., would have been saved to be used at a later date for another project. And perhaps the repairers were not averse to showing off a bit!

Two pieces of parchment fastened together with joining plait stitch (Engelberg, Stiftsbibliothek / Cod. 16 – Augustinus, Sermones ad populum diversi / f. 219r)plait stitch (Engelberg, Stiftsbibliothek / Cod. 16 – Augustinus, Sermones ad populum diversi / f. 219r)

However, what I found even more intriguing are the various manners in which gaps and holes were strengthened and/or filled, and yes, decorated. Some of the holes were bound with Cretan stitch, others with an open, buttonhole stitch (in this case also known as blanket stitch). In some cases the Cretan stitch and the open buttonhole stitch were used together with a starting ‘cord’ or bar.

A bar across the mouth of a parchment gap made from red silk bound with open buttonhole stitch in a light coloured thread (Engelberg, Stiftsbibliothek / Cod. 16 – Augustinus, Sermones ad populum diversi / f. 220r).

Another form of repair was the use of a form of needle weaving. In one example, the edges of a hole were strengthened with a buttenhole stitch, and a joining plait stitch to create zig-zags. The centre was filled with a yellow cross worked in darning stitch (needle weaving) to create the effect of a tabby weave ground (Engelberg, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. 61, fol. 98r; Sciacca 2010:69, fig. 3.11). The repair was worked in a combination of green, purple, salmon-pink and yellow silk. What is important is that this technique can be classed as a form of needle lace, as we know it from the sixteenth century onwards.

The following illustrations show a few of the ways used to strengthen slits, gaps and holes in Cod. 16 and Cod. 22, most of them using Cretan stitch and/or open buttonhole stitch. The result is, again, a form of needle lace:

Cretan stitch used to strengthen a parchment hole (Engelberg, Stiftsbibliothek / Cod. 16 – Augustinus, Sermones ad populum diversi / f. 81r).

A combination of joining plait stitch (left), and a hole (to the right) partially mended with a bar linked to a row of open buttonhole stitches. The buttonhole stitch was used to support a Cretan stitch filling (Engelberg, Stiftsbibliothek / Cod. 22 – Gregorius M., Moralia in Job, t. III / f. 33r).

Open buttonhole stitch (blanket stitch) in yellow used as an edging around the hole, to act as an anchor for a line of Cretan stitch in brown that was used to strengthen a parchment gap (Engelberg, Stiftsbibliothek / Cod. 22 – Gregorius M., Moralia in Job, t. III / f. 24r).

The needle lace character of some of the repairs is clear from the use of the button hole stitches. Most forms of needle lace are made of rows of open, buttonhole stitch in aria (i.e. without a cloth ground of some kind), a very good description of some of the holes in the parchment sheets.

A small parchment hole filled with Cretan stitch in a ‘lacy’ manner (Engelberg, Stiftsbibliothek / Cod. 16 – Augustinus, Sermones ad populum diversi / f. 108r).

So instead of looking to sixteenth century Italy, perhaps even Venice, for the origins of needle lace, as it is commonly cited and argued, could the history of needle lace be taken back to at least the mid-twelfth century, when it was used in Switzerland (and possible elsewhere) for darning and mending parchment codices while using up odd lengths of silk thread? After all, a more functional origin of forms of decorative needlework should not come as a surprise; the word 'embroidery' itself originates from a Germanic word for 'border' or 'edge', and reflects the use of needle and thread for strengthening, and perhaps decorating the edges of a piece of cloth.

A parchment gap strengthened and decorated with a bar, open buttonhole stitch and Cretan stitch, which create a ‘lacy’, red and yellow stripe and dot pattern (Engelberg, Stiftsbibliothek / Cod. 16 – Augustinus, Sermones ad populum diversi / f. 139r).

It should not be forgotten that Benedictine monks and nuns were known to travel vast distances, not to mention the books and codices they produced. So the transmission of this ‘mending’ idea from central Switzerland or elsewhere to neighbouring parts of Europe is not so far fetched.

And as needle lace is generally recognised as being the forerunner/ancestor of bobbin lace, could this mean that the history of bobbin lace may also be older than is currently suggested?

What is certain is that these manuscripts have opened a new line of research for me and perhaps for others as well. Something else to think about!

Text by Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood