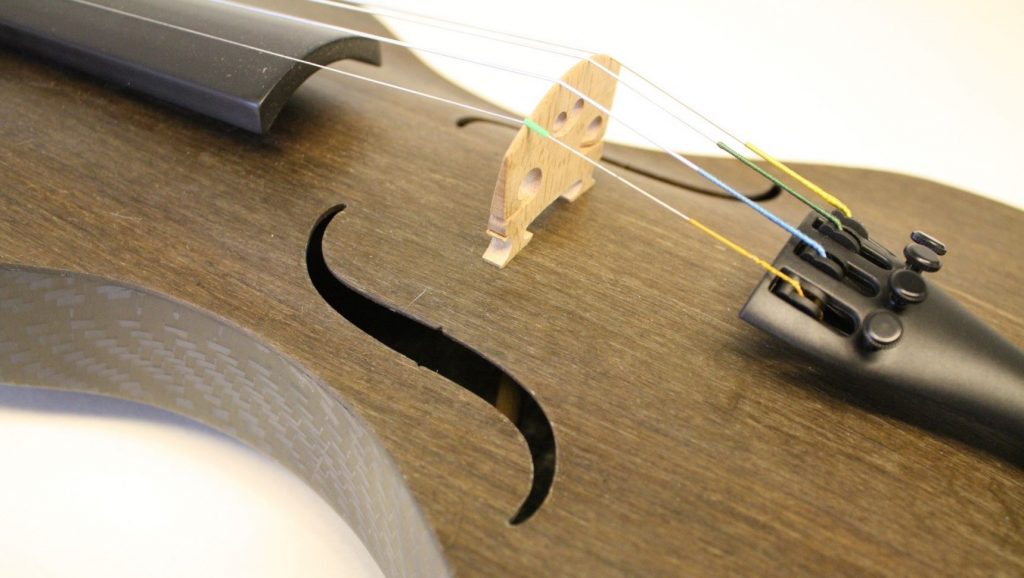

FLAX CELLO

Image: Flax cello by Tim Duerinck. Image courtesy of Tim Duerinck

Flax is best known as the plant from which linen is made and the Belgian town of Kortrijk in West Flanders has been at a centre of the European flax industry since the Middle Ages. Now a pop-up studio, in Texture, the town’s textile museum, itself a building converted from an authentic linen warehouse dating from 1912, has, however, created something amazing which has taken flax firmly into the 21st century - a playable cello.

Flax is one of the most sustainable and environmentally friendly plants; it will grow on poor soil, requires no irrigation, fertilisers, herbicides or pesticides and together with connecting resin it can be made into a very useful composite material. This is light and strong and at the museum there are example of several other items including a bicycle and car parts made from it.

The museum invited Tim Duerinck to undertake the making a cello from flax composite. Tim is a classical instrument-maker with an interest in using new materials to build instruments. He built a cello from polystyrene as part of his is master’s thesis at the university of Ghent.

Image courtesy of Ann Vanrolleghem

For this five month project in the museum’s TEXLAB#4 he liaised with textile designer, Esther van Schuylenbergh, to create the appropriate composite. Composition materials are made by merging two constituent materials having dissimilar properties in order to create a new finished material which is stronger and lighter than the more usual wood, stone and metal.

In this case it was made with pieces of mirror-twilled fabric layered with natural flax to create the patterns used when producing traditional wooden cellos. The pieces of fabric were then put into a mould and, using vacuum pressure, a resin was pumped through the mould and left to cure.

Esther further comments that this innovative design only marks the beginning of flax fibre’s musical capabilities.

“In my opinion there’s a lot more research to be done regarding structural efficiency: how thick and dense should the yarn be, and does it provide a structural advantage to the composition material?”

In fact, the process is so different from that used to construct a conventional wooden cello that a lot could go wrong. Luckily Tim’s experience and love of creative experimentation resulted in an instrument which is light, durable and most importantly, of pleasing acoustic quality.

Image courtesy of Mathieu Van de Sompel

Cellist and composer Benjamin Glorieux was responsible for testing and fine-tuning the instrument, after which he composed a new piece of music for it, based on old traditional flax songs from Texture's archive; songs which were originally sung to alleviate the hard work in the flax fields.

In July 2022, the cello was put on display in the Museum’s Wonder Room, accompanied by a mini documentary about its creation which can be watched here.

Visiting cellists are encouraged to make an appointment to come along and test-play this amazing cello at the Texture Museum of Flax and River Lys.

Blog courtesy of Patricia Cleveland-Peck

Flax is best known as the plant from which linen is made and the Belgian town of Kortrijk in West Flanders has been at a centre of the European flax industry since the Middle Ages. Now a pop-up studio, in Texture, the town’s textile museum, itself a building converted from an authentic linen warehouse dating from 1912, has, however, created something amazing which has taken flax firmly into the 21st century - a playable cello.

Flax is one of the most sustainable and environmentally friendly plants; it will grow on poor soil, requires no irrigation, fertilisers, herbicides or pesticides and together with connecting resin it can be made into a very useful composite material. This is light and strong and at the museum there are example of several other items including a bicycle and car parts made from it.

The museum invited Tim Duerinck to undertake the making a cello from flax composite. Tim is a classical instrument-maker with an interest in using new materials to build instruments. He built a cello from polystyrene as part of his is master’s thesis at the university of Ghent.

Image courtesy of Ann Vanrolleghem

For this five month project in the museum’s TEXLAB#4 he liaised with textile designer, Esther van Schuylenbergh, to create the appropriate composite. Composition materials are made by merging two constituent materials having dissimilar properties in order to create a new finished material which is stronger and lighter than the more usual wood, stone and metal.

In this case it was made with pieces of mirror-twilled fabric layered with natural flax to create the patterns used when producing traditional wooden cellos. The pieces of fabric were then put into a mould and, using vacuum pressure, a resin was pumped through the mould and left to cure.

Esther further comments that this innovative design only marks the beginning of flax fibre’s musical capabilities.

“In my opinion there’s a lot more research to be done regarding structural efficiency: how thick and dense should the yarn be, and does it provide a structural advantage to the composition material?”

In fact, the process is so different from that used to construct a conventional wooden cello that a lot could go wrong. Luckily Tim’s experience and love of creative experimentation resulted in an instrument which is light, durable and most importantly, of pleasing acoustic quality.

Image courtesy of Mathieu Van de Sompel

Cellist and composer Benjamin Glorieux was responsible for testing and fine-tuning the instrument, after which he composed a new piece of music for it, based on old traditional flax songs from Texture's archive; songs which were originally sung to alleviate the hard work in the flax fields.

In July 2022, the cello was put on display in the Museum’s Wonder Room, accompanied by a mini documentary about its creation which can be watched here.

Visiting cellists are encouraged to make an appointment to come along and test-play this amazing cello at the Texture Museum of Flax and River Lys.

Blog courtesy of Patricia Cleveland-Peck