IN THE CROSSHAIRS

When artist Rufina Bazlova travels on public transport in the Czech Republic, her home for the last thirteen years, she often gets out her sewing.

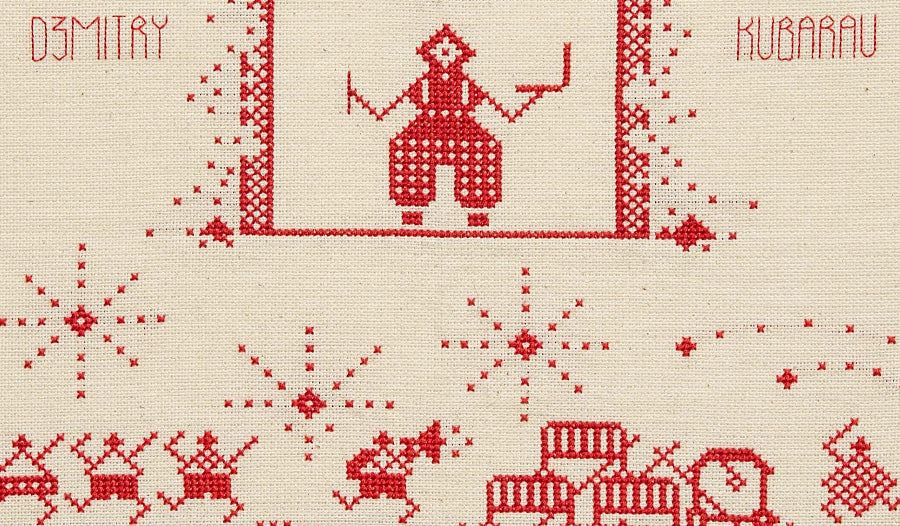

Produced in red thread on white linen in a cross-stitch formation, her embroidery shares stylistic elements with Slavic textile traditions, where red embellishments have long decorated ceremonial and ritual clothing and textiles in geometric grids and borders. Often older women on the bus will start conversations with Bazlova, politely enquiring about what she is making. The red decorative borders look familiar to them, but the stylised figures appear to be waving flags, pointing guns and using loudhailers.

Bazlova’s fellow passengers are surprised to hear that she is stitching symbolic portraits of each of the nine hundred plus political prisoners in her native Belarus, incarcerated for their participation in pro-democracy campaigns in and around 2020. Each embroidery depicts a named two-dimensional prisoner, trapped behind cross-stitched bars, with further dramatised detail provided of their so-called crime.

Through the sewing in her lap, the conversations between strangers turn to the current authoritarian regime under president Alyaksandr Lukashenka, whose heavy-handed tactics to stifle debate and critique have created a culture of fear and intimidation in the former Soviet state. The political prisoners, classified by human rights organisation Viasna (in English: Spring 96) include many of Bazlova’s friends – from bloggers to folk musicians–whose peaceful protests led to prosecution.

Bazlova’s mother and grandmother were talented seamstresses, weavers and knitters. Growing up in Grodno, like others in Belarus, Bazlova learned to sew at school. But her own creative practice – and the reason she moved to Prague to study – was originally in illustration.

Ten years ago, looking for new symbolic languages to explore, Bazlova began to explore motifs from folkloric textiles as a coded system for communicating, adapting their abstracted ornamental vocabularies into pictogrammatic figurative scenarios. She used these to create fictional myths about the life cycles of women, produced as a folded book but also sewn into sequential panels in a never-ending circle around the hem of a dress. The red thread on white ground conjured up enduring feminine experience but the visual language of the work she called Zhenokol (Feminnature) borrowed as much from comic strips and vector graphics as it did from village traditions.

Red-and-white has remained central to Bazlova’s palette across media forms. In the more politicised stitched body of work she has produced in recent years in response to the dictatorial crackdown in her home country, the colour pairing has taken on a further national dimension. The Belarusian flag of the People’s Republic, established in 1918 but later outlawed, is comprised of a single red horizontal stripe across a white base. This flag – superseded by Lukashenka’s official red and green banner – has become a symbol of grassroots protest; it featured regularly in the uprisings of 2020 against the totalitarian government, and her cross-stitched figures wave it in the blank space where massed protestors and armed police meet in the tense centre of the woven canvas. The History of the Belarusian Vyzhyvanka, the title of Bazlova’s protest series, contains a linguistic pun. Vyshyvanka is the name of a traditional embroidered Belarusian shirt but ‘vyzhyvat’ also means ‘to survive’.

Extract from the article In the Crosshairs: Rufina Bazlova's Cross-Stich Protest, written by Annebella Pollen. Read the rest of the article in the current issue of Selvedge, Issue 106 Identity

--