Mauka to Makai: Hawaiian Quilts and the Ecology of the Islands

Exploring the intimate relationship between Hawaiian quilts, post-colonialism and ecological disaster, research curator Marenka Thompson-Odlum traverses Hawai‘i through the Poakalani quilting group and fifteen extraordinary quilts, newly commissioned by Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, in her new book Mauka to Makai: Hawaiian Quilts and the Ecology of the Islands published by Common Threads Press.

The ahupua‘a is an ancient land division system — extending from the highest regions of Hawai‘i’s uplands (mauka) to the ocean (makai) — representative of the Hawaiian people's sacred knowledge and reverence towards the environment. Once a thriving and finely balanced system, the colonisation of the Hawaiian Islands coupled with the existential threat posed by the climate crisis has put the ahupua‘a severely at risk.

First established in 1972, the Poakalani quilting group continue to preserve the cultural legacy of Hawai‘i’s quilting tradition, sharing it with makers around the world. Featuring the stories behind the quilts and a glossary of Hawaiian words and phrases, alongside interviews with artists, activists, farmers and historians, Mauka to Makai: Hawaiian Quilts and the Ecology of the Islands pulls on the threads of connectivity shared by those who are using Indigenous Hawaiian philosophies of sustainable stewardship to revitalise the ahupua‘a.

Extract taken from Mauka to Makai: Hawaiian Quilts and the Ecology of the Islands (p.110-112)

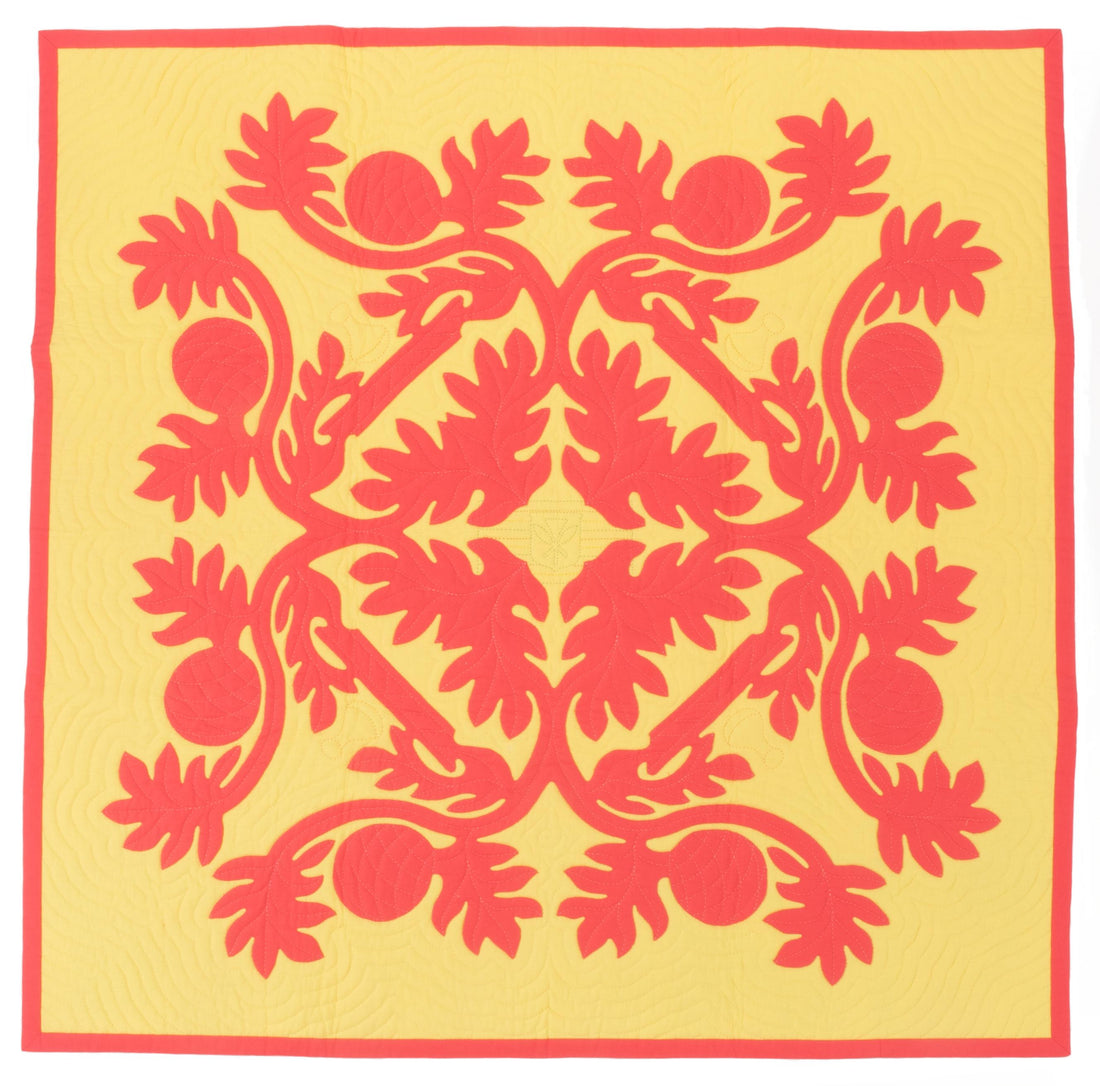

The Nā Mele ‘o Hula Kahiko quilt (left) depicts the instruments that traditionally accompany hula dancers — the pahu hula (drum), ‘ulī‘ulī (feathered rattles) and the pūniu (coconut knee drum). In contrast, hula ‘auana (contemporary hula) is known for its Western influences, including the use of musical instruments such as the guitar and ukulele. The word ‘auana literally means “to wander” or “to drift,” used here to communicate a drift away from the more sacred elements of hula kahiko (ancient hula). ‘Auana has become what most people globally think of as hula, solidifying the practice in perceptions of Hawaiian culture.

The journey of Mauka to Makai: Hawaiian Quilts and the Ecology of the Islands has highlighted the shifting sands of culture and of “authenticity.” Hawaiian quilting, like hula ‘auana, is a 19th–20th century creation that developed in response to outside influences — ever-changing but rooted in the knowledge of the kūpuna (ancestors). Notions of ‘authenticity’ and indigeneity are often problematically entangled.

When I first began this project, I faced many queries about how authentic the quilting was to Hawaiian culture. My choice of working with a practice that has a relatively short history (two hundred years) in the Hawaiian Islands was similarly called into question. I was reassured by a conversation I had with Hawaiian artist Solomon Enos, the son of Ka‘ala Farm's Eric Enos. As an artist whose work leans towards the graphic and the futurist, he too often faces the question of authenticity. His answer is simple: “I am continuing the work of my ancestors, just in a different medium.” That is the beauty of this culture. It can remain rooted in worlds of knowledge, whilst also making space for more people, ideas and means of expression — weaving the threads between the old and the new, the past and the present and the yet-unseen future.

There is a Hawaiian proverb, “I ka wā ma mua i ka wā ma hope” (“The future is in the past”), which describes the way in which many of the answers and solutions for our current questions reside in long-held traditions and knowledge. The saying hones in on a Hawaiian concept that runs throughout the stories represented in this book: the interconnectedness of all things, including time.

Many of the stories told in this text came about due to a disruption of that connectivity. Quilting was first introduced to Hawaiians by white American and European missionaries as a way to counteract nudity, which they viewed as a problem. At this time, Hawaiians already made their own fabric by the way of kapa (barkcloth), but this practice has since been disrupted and was for a long time thought to be lost. The ecological and social issues of species extinction, lack of water, wildfires and food insecurity as chronicled by these interviews can also be viewed through the lens of disruption — the disruption of a finely-connected and balanced ahupua‘a system. The physical, ecological and ideological colonisation of the Hawaiian Islands was perpetuated through the disruption of long-held knowledge.

Amongst all these weakened threads, the beauty remains that it is difficult to erase that which is so deeply rooted. Aloha ‘āina (love of the land, of place)

persists. Hawaiian quilting is proof that continued aloha ‘āina amidst monumental disruption can help to usher in a new form, a new quilting style which is specific to the archipelago. Still grounded in traditional Hawaiian aesthetics, the quilts pass down stories of the land, the people, resistance and resurgence.

Like these quilts, Ka‘ala Farm and Paepae o He‘eia are forging new paths in the face of disruption by looking to the past. In He‘eia, the definition of an ahupua‘a may have slightly expanded, but the spirit of community and mālama (responsibility) — both to your human and non-human neighbours — remains at its core.

The journey behind the creation of these fifteen quilts is centred on these threads of connectivity, weaving new ones, pulling on existing threads and imagining their possible pathways. I liken my Hawaiian quilting journey to the echo lines of a quilt: it began with one object, and over the last five years has reverberated to produce this book and create a beautifully diverse network of people and knowledge.

Sol Enos once told me, “the role of the hula dancer is as important as the community’s weavers and kapa makers, for the fabric of reality also needs frequent upkeep.”

It reminds me that everyone and everything has a purpose. The Poakalani quilting group, like the hula dancer, is stitching together the mo‘olelo of a place, of a people, of an ‘ohana.

Mauka to Makai: Hawaiian Quilts and the Ecology of the Islands published by Common Threads Press.

Find out more and order your copy:

www.commonthreadspress.co.uk

The ahupua‘a is an ancient land division system — extending from the highest regions of Hawai‘i’s uplands (mauka) to the ocean (makai) — representative of the Hawaiian people's sacred knowledge and reverence towards the environment. Once a thriving and finely balanced system, the colonisation of the Hawaiian Islands coupled with the existential threat posed by the climate crisis has put the ahupua‘a severely at risk.

First established in 1972, the Poakalani quilting group continue to preserve the cultural legacy of Hawai‘i’s quilting tradition, sharing it with makers around the world. Featuring the stories behind the quilts and a glossary of Hawaiian words and phrases, alongside interviews with artists, activists, farmers and historians, Mauka to Makai: Hawaiian Quilts and the Ecology of the Islands pulls on the threads of connectivity shared by those who are using Indigenous Hawaiian philosophies of sustainable stewardship to revitalise the ahupua‘a.

Extract taken from Mauka to Makai: Hawaiian Quilts and the Ecology of the Islands (p.110-112)

The Nā Mele ‘o Hula Kahiko quilt (left) depicts the instruments that traditionally accompany hula dancers — the pahu hula (drum), ‘ulī‘ulī (feathered rattles) and the pūniu (coconut knee drum). In contrast, hula ‘auana (contemporary hula) is known for its Western influences, including the use of musical instruments such as the guitar and ukulele. The word ‘auana literally means “to wander” or “to drift,” used here to communicate a drift away from the more sacred elements of hula kahiko (ancient hula). ‘Auana has become what most people globally think of as hula, solidifying the practice in perceptions of Hawaiian culture.

The journey of Mauka to Makai: Hawaiian Quilts and the Ecology of the Islands has highlighted the shifting sands of culture and of “authenticity.” Hawaiian quilting, like hula ‘auana, is a 19th–20th century creation that developed in response to outside influences — ever-changing but rooted in the knowledge of the kūpuna (ancestors). Notions of ‘authenticity’ and indigeneity are often problematically entangled.

When I first began this project, I faced many queries about how authentic the quilting was to Hawaiian culture. My choice of working with a practice that has a relatively short history (two hundred years) in the Hawaiian Islands was similarly called into question. I was reassured by a conversation I had with Hawaiian artist Solomon Enos, the son of Ka‘ala Farm's Eric Enos. As an artist whose work leans towards the graphic and the futurist, he too often faces the question of authenticity. His answer is simple: “I am continuing the work of my ancestors, just in a different medium.” That is the beauty of this culture. It can remain rooted in worlds of knowledge, whilst also making space for more people, ideas and means of expression — weaving the threads between the old and the new, the past and the present and the yet-unseen future.

There is a Hawaiian proverb, “I ka wā ma mua i ka wā ma hope” (“The future is in the past”), which describes the way in which many of the answers and solutions for our current questions reside in long-held traditions and knowledge. The saying hones in on a Hawaiian concept that runs throughout the stories represented in this book: the interconnectedness of all things, including time.

Many of the stories told in this text came about due to a disruption of that connectivity. Quilting was first introduced to Hawaiians by white American and European missionaries as a way to counteract nudity, which they viewed as a problem. At this time, Hawaiians already made their own fabric by the way of kapa (barkcloth), but this practice has since been disrupted and was for a long time thought to be lost. The ecological and social issues of species extinction, lack of water, wildfires and food insecurity as chronicled by these interviews can also be viewed through the lens of disruption — the disruption of a finely-connected and balanced ahupua‘a system. The physical, ecological and ideological colonisation of the Hawaiian Islands was perpetuated through the disruption of long-held knowledge.

Amongst all these weakened threads, the beauty remains that it is difficult to erase that which is so deeply rooted. Aloha ‘āina (love of the land, of place)

persists. Hawaiian quilting is proof that continued aloha ‘āina amidst monumental disruption can help to usher in a new form, a new quilting style which is specific to the archipelago. Still grounded in traditional Hawaiian aesthetics, the quilts pass down stories of the land, the people, resistance and resurgence.

Like these quilts, Ka‘ala Farm and Paepae o He‘eia are forging new paths in the face of disruption by looking to the past. In He‘eia, the definition of an ahupua‘a may have slightly expanded, but the spirit of community and mālama (responsibility) — both to your human and non-human neighbours — remains at its core.

The journey behind the creation of these fifteen quilts is centred on these threads of connectivity, weaving new ones, pulling on existing threads and imagining their possible pathways. I liken my Hawaiian quilting journey to the echo lines of a quilt: it began with one object, and over the last five years has reverberated to produce this book and create a beautifully diverse network of people and knowledge.

Sol Enos once told me, “the role of the hula dancer is as important as the community’s weavers and kapa makers, for the fabric of reality also needs frequent upkeep.”

It reminds me that everyone and everything has a purpose. The Poakalani quilting group, like the hula dancer, is stitching together the mo‘olelo of a place, of a people, of an ‘ohana.

Mauka to Makai: Hawaiian Quilts and the Ecology of the Islands published by Common Threads Press.

Find out more and order your copy:

www.commonthreadspress.co.uk