SACRED AND PROFANE

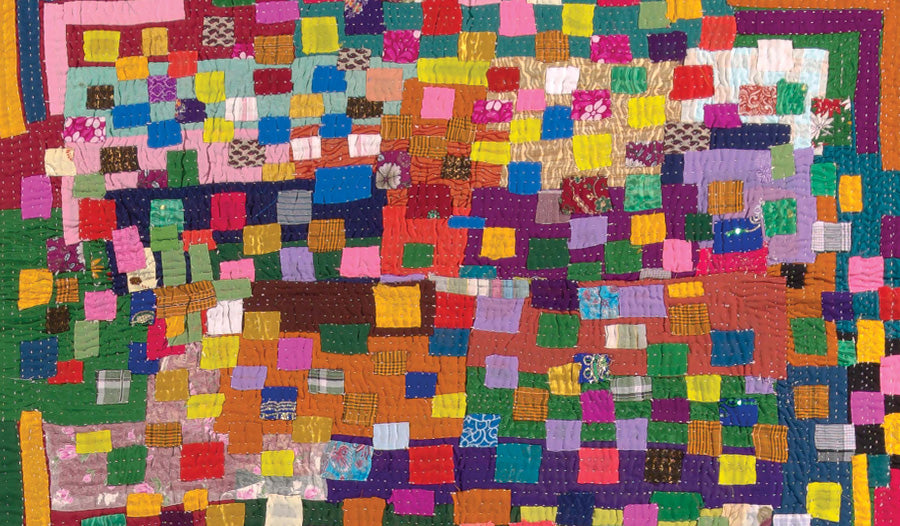

The running stitch is universal; artisans all over the world have adapted and integrated this stitch into their local craft traditions. It is multipurpose, as it unites several layers of fabric while it embellishes the cloth with a sculpted, yet soft, texture. One tradition that stands out is the patchwork quilt, known by many different names in India. These patchworks are used as both mattresses and covers and made by women for their children and grandchildren. These quilts, called godharis, are essentially made from everyday pieces of cloth, patched together to reinforce the worn areas. Makers add layer upon layer of reused cloth from old saris to provide warmth and durability. Born out of necessity, the materials are stretched to their limits and reinforced with stitches. Using a heavy gauge cotton thread, the running stitch is worked through the multiple layers of cloth.

The in-between layers, or batting, are filled with used trousers and shirts ripped open and laid out flat. Unlike the Bengal Kanthas, no figures, flowers, gods or goddesses are depicted. Most of the godharis are abstract in form, revealing rows and rows of torn straight stripes of cloth, often slit with old razor blades. Each godhari is therefore unique, as no assemblage of repurposed fabric is ever the same. In keeping with the ‘make and make do’ practice of this craft, the women find little use in standard forms of measurements. Rather, they rely on the ergonomics of their hands and fingers, with the tips of the finger to the elbow equaling a half yard, for example. It requires a keen intelligence to be able to use what is available, and recycle everyday items into something as practical and beautiful as a godhari.

Image: Courtesy The International Quilt Museum, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Image: Courtesy The International Quilt Museum, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

It would be odd to see these quilts made of expensive materials like silk or velvet. Rather, godharis are typically simple, functional quilts. and as mentioned, constructed using strips of old cotton. The women utilise their fine skills to appliqué strips of fabric, creating a pattern that slowly emerges. Smaller godharis are made from a mother’s old saris and are traditionally used to cover and protect a newborn child. The smell and feel of the mother’s old saris give the baby an added sense of security; her presence is palpable for the child. These patchworks therefore straddle the line between the sacred and the profane.

After a day’s work of providing for the household and stitching during their free time, the women roll their works in progress onto a large, thick wooden rod. The godharis are then held down with large stones to keep the quilt stretched flat. The making of godharis is often communal, providing a practical excuse for women to get together to entertain themselves and exchange local news and recipes–and gossip, of course. Sometimes, three to four women will sit together to quilt, beginning from the outer edge and working towards the centre of the quilt. Embedded in tradition, the Maharashtrian women chant a mantra or folk song as they sew along. Again, these practical yet spiritual practices creates a unique link between the makers and the users.

Image: This quiltmaker—the wife of an itinerant fortune-teller from the Joshi ethnic group, Wai, a village below the hill station — has created an interpritation of a kundali or astrological chart by superimposing coloured strips to form the planetary ‘houses’ over the design of concentric squares.

In keeping with tradition, the godharis are washed communally twice a year–before monsoon season in May, during the festival of Mahashivaratri, and after the monsoon rains have subsided around end of September, during the festival of Dassera. The quilts are washed using the flow of the river and then dried in the sun. Perhaps this ritualistic cleansing of manmade, household objects allows the communities to nourish a deeper connection with the natural cycles of their land.

Researcher Geeta Khandelwal has travelled to thirty or more remote villages in Maharashtra, India to meet and interview the local quilters of the region. She completed three years of extensive search into godharis–often walking under the sweltering sun and heavy rains–until a patchwork of images and stories began to emerge. This culminated in the book Godharis of Maharashtra, Western India, published by Quiltmania Editions in 2013. This unique collection was one of the first attempts to research the humble godharis of Maharashtra, showcasing this relatively unknown rural craft with the global community and lending it its due acknowledgement and dignity.

Image: Katumbi Sharief, Siddi, Mainalli, Mundgod, Uttar Kannad. Although Siddi quiltmakers all follow the same basic format and method of construction, they often add supplementary design elements. Some apply tikeli (small, brightly colored squares) onto of the first layer of patches for extra ornament. Others decorate their corners with multiple, L -shaped brackets, a motif said to be popular among Muslim Siddi. Gift of the Robert and Ardis James Foundation.

Khandelwal shares: ‘Quilting is both creative and spiritual. I believe that the quilter enters into a private relationship between herself and her creation. And the outcome evolves as a dialogue between the two. The quilts serve a two-fold purpose –they provide an outlet of creativity; more importantly, they sing the glory of the faceless women.’

With their long strips of colourful fabrics that create rainbows of abstract, geometrical forms, the godharis might run the risk of misinterpretation within the Western gaze. Similar to the widespread popularity of boro fabrics from Japan, it would be easy to admire these abstract forms with mere visual, intellectual fascination. After all, there are many parallels that could be drawn between godharis and Modern western art. However, this would miss the true depth of meaning that is sewn in every stich. The value of these quilts is represented in the layers and layers of worn fabrics, artfully combined to create something that warms us, body and soul.

Excerpt from the article Sacred and Profane: The Godharis of Maharashtra, in Issue 105 Checks & Stripes.

1 comment

Most interesting informative article on a much admired textile practice Love the emphasis of artistic intuition which plays such a part in the success of these beautiful works by amazing women