THE HISTORY BOOKS

Are there any descriptions of fashion or clothing in literature that have particularly struck you?

Perhaps this is an irrelevant question. Often maligned as irrelevant and reserved only for the frivolous, vain, flighty and yes, dim, we here know fashion is actually a very serious business.

It is a vital component of socio-cultural communication on pretty much every level. Think of it as a capillary system of a primarily visual, tactile language that permeates every strata of society and culture, which everyone over 18 months old understands in some way. Fashion is understood by even those who deny an interest in fashion, or who choose not to wear clothes at all because the language of fashion has to be understood in the first place, for it to be rejected. Who can forget the scene from The Devil Wears Prada in which the terrifying editor, Miranda Priestley frostily explains to a new, fashion indifferent assistant her perspective of trend trickle-down theory aka ‘the cerulean blue belt treatise’? The scene was created by scriptwriters rather than the book’s author Lauren Weisberger, but as a reference to the socio-economic and hierarchical structures of fashion, it is pitch perfect.

It is a theme well used in literature, from the classics of Ancient Greece through Romanticism and Victorian Gothic, to contemporary tales of identity and place. Homer describes the fashionable women of Ancient Greece as being dressed in beautiful and costly sashes that set them apart from the ordinary Joannas, and Sappho wrote an entire poem based on fashion trends as a guide for her supposed daughter. A couple of hundred years later Thucydides and others of his generation decided that things had become somewhat decadent, excessive and democratic (golden grasshopper hair scrunchies for guys, anyone?). So, they adopted the simple, shorter woollen tunic, or chiton style worn by poorer men. Incapable of maintaining total social integration, Thucydides and his contemporaries knowingly modelled their new threads with a pop of minimal, Ancient Greek chic by way of finer fabrics and accessories.

Image: The Great Gatsby (2013)

Image: The Great Gatsby (2013)

Not knowing the inherent rules of class separation can be disastrous, as demonstrated by F. Scott Fitzgerald’s enigmatic protagonist Jay Gatsby, who masquerades as an old money ‘Oxford Man’. He claims to belong amongst a particularly elevated American social class but despite his wealth and fashionably lavish lifestyle falls foul of sartorial codes known only within that elite group. His crime is to wear a flamboyant, beautifully tailored pink suit that blows his disguise and identifies him as an arriviste. Like his creator, a Princeton graduate from a modest background Gatsby, as described by the scholar Matthew Bruccoli, ‘is in the club on only a guest membership’.

The young character of the Artful Dodger in Dicken’s Oliver Twist knew how to use clothes to fashion a streetwise and savvy persona, and how to perform as a confident, swaggering male in his garments. Dickens writes him as clothed in a man’s coat, with a cocked, ill-fitting top hat and corderoy trousers whose pockets his hands were stuffed into, when they weren’t picking the pockets of others. Positioning his hands in such a way would cause the coat to gather and swing behind him. Dickens tells us about the Artful Dodger’s manner and gait by relying on a widely known, as well as temporally flexible, recognition of fashion’s multifaceted language. Similarly, like a defiant schoolboy, Vita Sackville-West was known to stride about in a coat with her hands in her trouser pockets. This is the performative satisfaction of ‘hands in pockets, swirly, long coat’ swagger.

Image: James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Symphony in White No.1: The White Girl (detail) , 1862. Oil on canvas. 213 x 107.9 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Harris Whittemore Collection.

Image: James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Symphony in White No.1: The White Girl (detail) , 1862. Oil on canvas. 213 x 107.9 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Harris Whittemore Collection.

Fashion and clothing is so very important to literature because it sets the scene for us, it contextualises characters and a good description of clothing provides not only a readable drawing, or visual perception of a character but it can activate other sensory, as well as emotional responses. The pitiful, jilted bride Miss Havisham in Great Expectations, still dressed in her mouldering wedding outfit after several decades evokes mustiness, dustiness, gloom, and a perpetual silence. Miss Havisham’s out of place clothing and its decaying condition identifies her as deranged in some way, a condition often attributed to female characters by male authors....

Wilkie Collin’s The Woman in White is one such example of female derangement and Anne Catherick is the titular character who, believed to hold a powerful secret, is driven to her mental disturbance by incarceration at an asylum. The story of her preference for all white clothing is situated in happy moments of her childhood and like Miss Havisham’s wedding gown, suggest purity and youth. The muslin of Anne Catherick’s ethereal dresses also relates to the fashion and economic events of the time. Mid-1850’s Britain was a colonial power and exotic, imported fabrics such as muslin that demonstrated that reach and power, were popular choices for women who could afford them.

However, as well as indicating the status of Catherick, the daughter of a gentleman and a maid, and the family to which she belongs, the white, diaphanous nature of her clothing creates a ghostly image that portends her fate. It signifies her fragility, which is actually rather more physical than mental and provides a blank canvas upon which tropes of disturbance, threat, haunted-ness and dislocation might be situated.

The language of fashion in contemporary literature seems to be more complex in terms of themes but apparently hinges around identity and identification supported by various social, cultural, economic, and ethnic structures...

Extract from the article The History Books: Fashion and Literature from Issue 90 West, written by Dr Nicole Donovan.

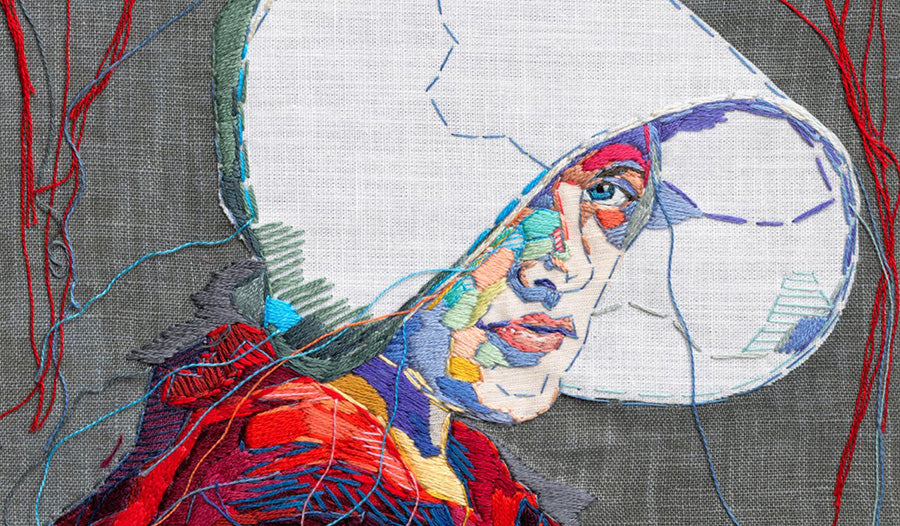

Lead image: Artist Lauren Dicioccio’s embroidered portrait of Elisabeth Moss as Offred from the TV adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s novel, The Handmaid’s Tale.

--

Did you enjoy this article? Our first Textile Literary Festival will comprise three acts, one of which will explore fiction that features textiles through narratives. Visit out event page to discover some of the fantastic authors and writers taking part in the festival.

The Selvedge Textile Literary Festival takes place on Saturday 2 April 2022.