GRAYSON PERRY: POSH CLOTHS

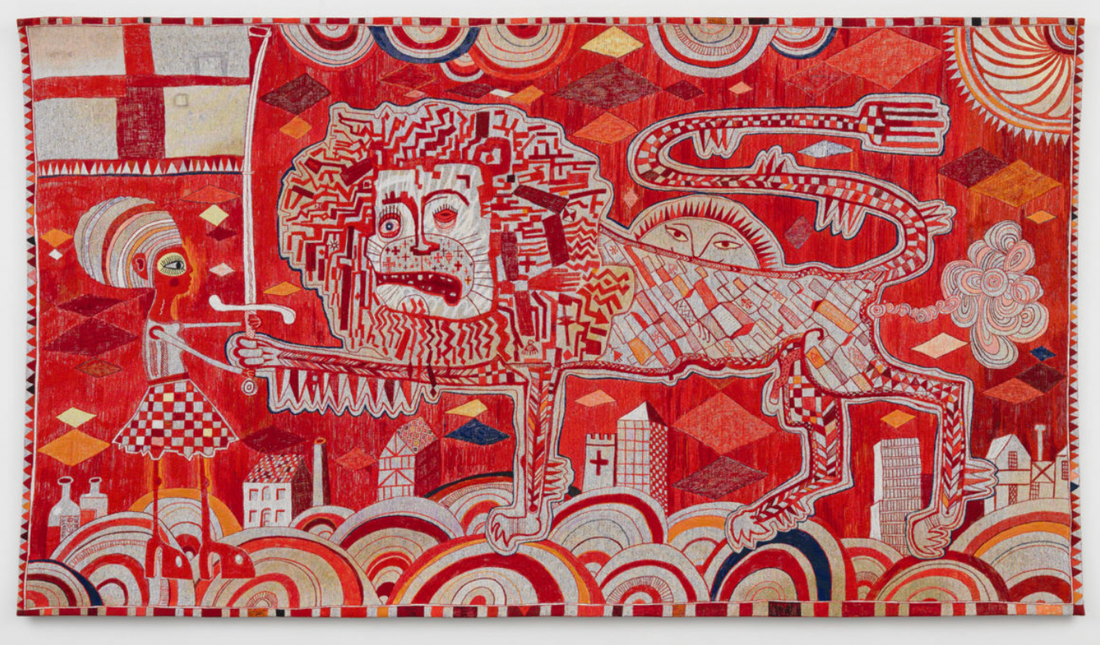

Grayson Perry, 'Sacred Tribal Artefact', 2023, Tapestry, 200 x 350 cm, 78 3/4 x 137 3/4 in

Guest edited by Deborah Nash

Grayson Perry: Posh Cloths is on show at London Victoria Miro Gallery until 25 March 2023

Leaving London’s Victoria Miro gallery in early February, I crossed Grayson Perry in the doorway, whose nine tapestries I’d just seen displayed across two floors. He barrels through, looking hurried and slightly harassed. Perry has currently two exhibitions on the go: tapestries in London, pots, sculptures and sketches of urban foxes in Venice, and his latest television series Full English is on Channel 4. He’s a one-man art production show, slipping between different media as naturally as he slips on a dress to become Claire. Like other British artists of his generation – Damien Hirst, Antony Gormley, Anish Kapoor – Perry’s output is not only prodigious but also, with his tapestries, on an increasingly large scale.

His first, The Walthamstow Tapestry, took as its theme the invasion of brands into our daily lives. Six more followed during the making of a television series on taste. “Tapestry is the art form of grand houses,” he says. “On my television taste safari, I only saw tapestries hanging in stately homes. They depicted classical myths, historical and religious scenes or epic battles like Hannibal crossing the Alps. I enjoy the idea of using this costly and ancient medium to show the commonplace dramas of modern British life.”

So, the medium becomes the message, part of Perry’s lexicon of irony and satire. He builds social commentary into his artworks as did the 18th century moralising painter and printmaker William Hogarth, whose A Rake’s Progress finds its 21st century equivalent in The Vanity of Small Differences 2012.

In Posh Cloths the artist depicts marginalised communities broken by internal strife and external pressures (The Digmoor Tapestry, 2016). He flags up the corrosion of culture in the metropolis by labelling the contrasting forces defining London life – gig economy, modern-day slavery, rent-seeker, gentrification, globalisation, unregulated market (Large Expensive Abstract Painting, 2019). The organising principle of these works is often the map, be it of London, Manhattan, Essex or Digmoor Estate. Place is important to Perry, who trawls through England’s marbled heritage of the historic and the present-day and its mulch of different peoples. Describing himself as ‘a detail freak’ the artist is both story-teller and sharp visual chronicler of a fragmented nation.

A Lion Passé: Sacred Tribal Artefact, 2023 Grayson Perry, 'In its Familiarity, Golden', 2015, Tapestry, 290 x 343 cm, 114 1/8 x, 135 1/8 in

Grayson Perry, 'In its Familiarity, Golden', 2015, Tapestry, 290 x 343 cm, 114 1/8 x, 135 1/8 in

Inside the Victoria Miro I’m particularly drawn to the most recent weaving Sacred Tribal Artefact, 2023. Like an Asafo flag, a battered heraldic lion holds the St George’s flag attached to a sword that is being taken by a young woman of colour – the future generation. The lion is in a sorry state with a punched-out eye, broken teeth, tiny crusader crosses where its whiskers grow, flaccid prick, and a nuclear explosion of a fart. On its back, the sun is sinking. Behind it, an old church, Tudor-framed cottages and a dead factory chimney jostle for space next to Canary Wharf tower and tower blocks. The old symbols of nationhood and power are in need of a refresh.  Grayson Perry, 'Large Expensive Abstract Painting', 2019, Tapestry, 200 x 300 cm, 78 3/4 x 118 1/8 in

Grayson Perry, 'Large Expensive Abstract Painting', 2019, Tapestry, 200 x 300 cm, 78 3/4 x 118 1/8 in

A Palimpsest: Morris, Gainsborough, Turner, Riley, 2021

Two tapestries on display feature well-known masterpieces held in our national collections. In Morris, Gainsborough, Turner and Riley, Perry has collaborated with Factum Arte in Madrid to digitally alter works by four English artists from different eras – the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries - and layer them on top of each other to create tantalising glimpses of their parts that rise to the surface or fall back into the shadows, as if the tapestry itself has a certain fluidity, like a pool of water stirred with a stick. In this way, Thomas Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews, a portrait of landed gentry who own all that you see in the original canvas, are partially obscured by Bridget Riley’s Op Art stripes, an abstract painting style that arrived in the 1960s, an oblique reference to new movements and ideas in art-making replacing the old. Representing a departure from doomster humour, this tapestry encourages a slow unpicking of the individual artworks but their digital reproduction is limiting at times, making them more satisfying to view in flattened online form.

England on the Skids: Battle of Britain, 2017

Grayson Perry, 'Battle of Britain', 2017, Tapestry, 293 x 675 cm, 115 3/8 x 265 3/4 in

A cyclist looks down on maimed countryside bent to man’s will, bisected by rail tracks, A-road, fenced fields, pylons, turbines and silos and a deserted playground; a queue of traffic to the east processes towards the Eurostar tunnel, a murmuration of starlings flies through dark polluting clouds, a burnt-out car adds to the mix, while the graffiti shouts ‘Toffs Out!’ This world overlays ghost images of decorative textiles, ones you might more happily sleep beneath or tread upon.

“I have always enjoyed the in-between places or “edgelands” as they have become fashionably known,” says Perry of this tapestry. “The imaginary place I have depicted is not unlike the landscape of Essex where I lived as a young child.”

Woven post-Brexit, Battle of Britain evokes a circumscribed narrowed world where troubles are embedded in the view. Unlike the aerial dog fights of Paul Nash’s Battle of Britain 1941, which led to victory in World War II, here the prevailing mood is one of despondency and defeat.

The Noblest of Weaving Arts? Grayson Perry, Very Large Very Expensive Abstract Painting, 2020, Tapestry, 292 x 688 cm, 115 x 270 7/8 in

Grayson Perry, Very Large Very Expensive Abstract Painting, 2020, Tapestry, 292 x 688 cm, 115 x 270 7/8 in

Grayson Perry is among several contemporary artists revitalising the craft of tapestry. In 2017, fellow Turner Prize winner, Chris Ofili, presented The Caged Bird’s Song at the National Gallery, which he described as a ‘watercolour in wool’. The loose, dreamlike design of wool, cotton and viscose took more than two years to make on the hand loom at Edinburgh’s Dovecot Studio. By contrast, Perry’s designs are produced by computer-operated machinery in Belgium, a much swifter process, but also one that leads to a slicker aesthetic. Arguably, there’s an absence of emotional connection to the medium, the textural qualities of the threads, the fact that a tapestry is not a copy of a drawing or painting, that a tapestry is linked, as its champion Jean Lurçat affirmed, to its architectural setting.

Perry’s political critiques also have precedent. Norwegian textile artist Hannah Ryggen repeatedly sounded the alarm on fascism from her farmhouse on the Fjords in the 1930s and 40s, where she hand-dyed yarns and wove tapestries that depicted Mussolini, Hitler and the concentration camps, among other subjects. In today’s Britain, the effects of gentrification are well-known, but identity politics and the cost of living crisis has led to further fragmentation, while trust in our institutions – the police, the royal family, the BBC, the political class – has been undermined by repeated exposures of misdeeds. Meanwhile, anxiety over issues that extend well beyond our shores – sustainability versus oil and gas companies, war, climate change and environmental catastrophe – is on the rise.

Commenting recently in the FT on the use of tapestry in contemporary fashion, design historian and curator Marta Franceschini noted: “We are negotiating our position between digital and physical…. The styles emerging are a mix of historical references to reassuring traditions and creative interpretation of what the future might mean.”

Grayson Perry has captured the precariousness of disenfranchised lives but has the proliferation of his multimedia brand gentrified its subjects?

Grayson Perry: Posh Cloths is on show at London Victoria Miro Gallery until 25 March 2023