Soldiers in Petticoats

Released in October 2015, Suffragette stars Meryl Streep as the figurehead of the fight for women’s right to vote, Emmeline Pankhurst, and also Carey Mulligan and Helena Bonham Carter as other prominent activists. Of interest to many viewers will be the depiction of contemporary costume, and in the film Streep as Pankhurst is shown dressed in subdued, respectable clothing accessorised with a silver medal complete with ribbon in the Suffragette colours of green, purple and white.

Although for some the word ‘suffragette’ might bring to mind images of Edwardian, middle class ladies chained to railings, or the horrific, grainy pictures of Emily Wilding Davison suffering fatal injuries from the King’s horse at the 1913 Derby, this resistance movement also operated as a sophisticated political organisation. Actually called by its members the ‘Women’s Social and Political Union’, who were themselves dubbed ‘Suffragettes’ by the Daily Mail, this organisation chose its colours as a means to covertly, and also overtly, indicate solidarity. The colours, which were chosen to represent dignity and freedom (purple), purity in public and private life (white) and hope and newness (green), created a sense of unity, which was something that many women of the time had not yet experienced.

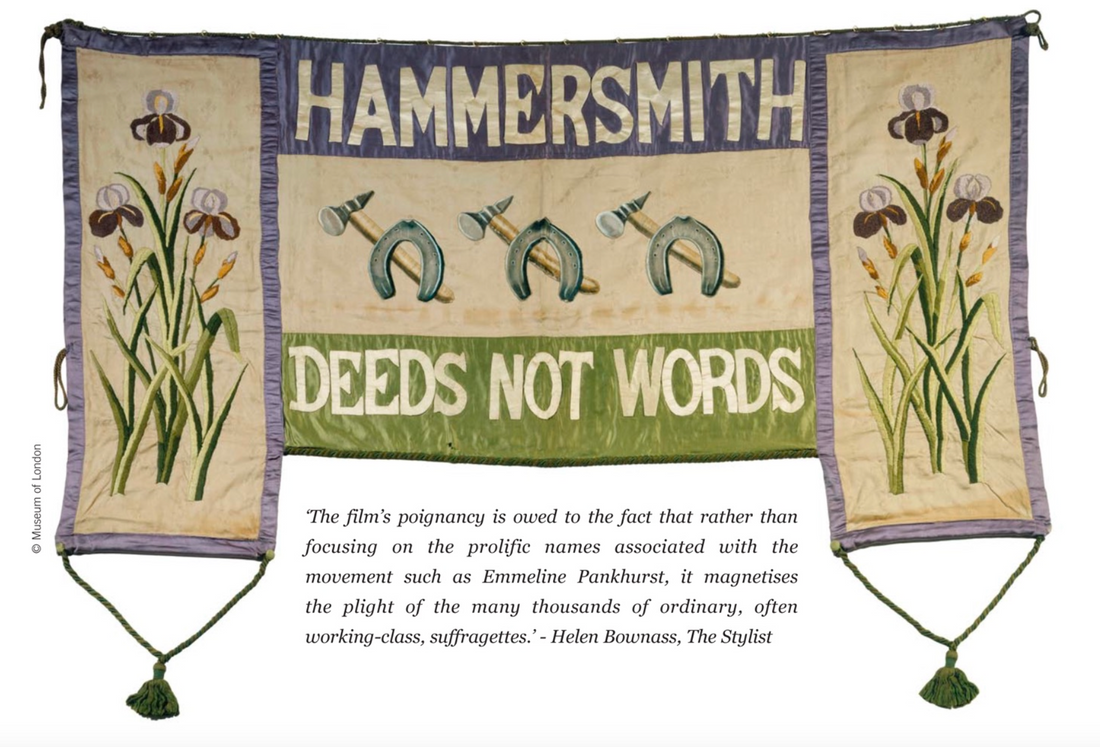

Image: Carey Mulligan as Maud Watts in Suffragette directed by Sarah Gavron 2015. Image above: Suffragette banner of the Hammersmith branch of the militant Women's Social and Political Union.

Expression of this new commonality amongst women appeared in the form of textile crafts and is particularly visible in the embroidered, stencilled and appliquéd banners that identified ‘chapters’ of the Women’s Social and Political Union. The banners were used to promote The Causein processions and marches, or used as templates for printed leaflets. The collaboratively produced banners would carry beautifully crafted slogans such as ‘Votes for Women’, ‘Believe and You Will Conquer’ and the notorious call for violent protest – ‘Deeds, not Words’. Some banners were even woven and there are some intriguing examples of these held in the Women’s Library at the London School of Economics (LSE) Suffragette banner collection.

The purple, white and green emblematic colours tended to be worn as accessories, especially among working-class women who could not afford the white dresses worn by wealthier suffragettes, or their beautiful amethyst, emerald and pearl jewellery. However, some women wore an all-over version of their allegiance to ‘the cause’ as exemplified by the suffragette dress made by Leonora Cohen, who not only wore it to the Arts Society Ball in 1914, but also sealed her notoriety by smashing the case that held the Crown Jewels in the Tower of London. The garment is a simple, kimono style and modelled on the lines of aesthetic dress, which was intended to allow freedom from the constraints of conventional women’s clothing, such as tight corsets and bulky, or hobbled skirts.

Cohen’s dress is of course green, purple and white, and is splashed across its front with the words ‘Suffragette’ and ‘Justice’, along with the initials ‘W.S.P.U.’ Together with the garment’s loose form this bold declaration of resistance and indeed allegiance, would have made a radical and perhaps scandalous statement at a time when women were expected to behave otherwise. Speaking to Jess Cartner-Morley in The Guardian, Donna Loveday, co-curator of the Women Fashion Power exhibition at the Design Museum, points out that the suffragettes ‘chose to embrace femininity in their dress, because they were monstered for being unnatural and mannish, and to counterbalance that they had a deliberate tactic of dressing in a conventional, ladylike way. There’s a sense of power coming from embodying your gender, not denying it.’

Image: Leonora Cohen, 1873-1978 Suffragette Dress, 1914, rayon & paper of London.

Image: Leonora Cohen, 1873-1978 Suffragette Dress, 1914, rayon & paper of London.

Practical or mundane garments such as floor length aprons were also emblazoned with slogans and declarations of allegiance to the fight for the right to vote. However, these domestic, embellished items brought scorn and abuse upon the defiant women who wore them to go about day-to-day duties within and beyond the home. Wearing accessories in suffragette colours was not confined only to women, and men who supported the fight for women to have the right to vote ported the purple, green and white as ties, scarves, or hatbands.

The women who led the suffragette movement tended to be from the middle and upper classes. It is acknowledged that they were the women who could afford to take the time and bear the financial costs that were necessary to campaign and drive The Cause. Although cotton mill workers from Pankhurst’s native Manchester could not spare the time to march, and indeed fell away from the movement after Emmeline’s departure for London, she and her (militant) daughter Christobel still marched for all women’s right to vote.

What is sometimes forgotten is that during the Great War, suffragettes suspended activism and instead directed their energies to supporting the Country. They were encouraged by the movement’s leading members to volunteer for essential work such as in munitions factories and transport. For this contribution they earned the belief of government that women could be given responsibility, and could possibly make an informed decision.

So, at the end of World War 1 in 1918, ‘respectable’ ladies over 30 years old who were householders, or married to householders, were given the vote. 10 years later, in 1928, The Representation of The People Actmade women’s voting rights equal with men. The Suffragettes, their forebears, the Suffragists and the Blue Stocking before them (see Selvedge Issue 28) have enabled women today to have a voice and the right to place an X in a box on voting day.

Guest edited by Nicola Donovan

Nicola Donovan pins down the subversive style of the Suffragettes: Soldiers in Petticoats was first published in Selvedge issue 67, Migration.

Although for some the word ‘suffragette’ might bring to mind images of Edwardian, middle class ladies chained to railings, or the horrific, grainy pictures of Emily Wilding Davison suffering fatal injuries from the King’s horse at the 1913 Derby, this resistance movement also operated as a sophisticated political organisation. Actually called by its members the ‘Women’s Social and Political Union’, who were themselves dubbed ‘Suffragettes’ by the Daily Mail, this organisation chose its colours as a means to covertly, and also overtly, indicate solidarity. The colours, which were chosen to represent dignity and freedom (purple), purity in public and private life (white) and hope and newness (green), created a sense of unity, which was something that many women of the time had not yet experienced.

Image: Carey Mulligan as Maud Watts in Suffragette directed by Sarah Gavron 2015. Image above: Suffragette banner of the Hammersmith branch of the militant Women's Social and Political Union.

Expression of this new commonality amongst women appeared in the form of textile crafts and is particularly visible in the embroidered, stencilled and appliquéd banners that identified ‘chapters’ of the Women’s Social and Political Union. The banners were used to promote The Causein processions and marches, or used as templates for printed leaflets. The collaboratively produced banners would carry beautifully crafted slogans such as ‘Votes for Women’, ‘Believe and You Will Conquer’ and the notorious call for violent protest – ‘Deeds, not Words’. Some banners were even woven and there are some intriguing examples of these held in the Women’s Library at the London School of Economics (LSE) Suffragette banner collection.

The purple, white and green emblematic colours tended to be worn as accessories, especially among working-class women who could not afford the white dresses worn by wealthier suffragettes, or their beautiful amethyst, emerald and pearl jewellery. However, some women wore an all-over version of their allegiance to ‘the cause’ as exemplified by the suffragette dress made by Leonora Cohen, who not only wore it to the Arts Society Ball in 1914, but also sealed her notoriety by smashing the case that held the Crown Jewels in the Tower of London. The garment is a simple, kimono style and modelled on the lines of aesthetic dress, which was intended to allow freedom from the constraints of conventional women’s clothing, such as tight corsets and bulky, or hobbled skirts.

Cohen’s dress is of course green, purple and white, and is splashed across its front with the words ‘Suffragette’ and ‘Justice’, along with the initials ‘W.S.P.U.’ Together with the garment’s loose form this bold declaration of resistance and indeed allegiance, would have made a radical and perhaps scandalous statement at a time when women were expected to behave otherwise. Speaking to Jess Cartner-Morley in The Guardian, Donna Loveday, co-curator of the Women Fashion Power exhibition at the Design Museum, points out that the suffragettes ‘chose to embrace femininity in their dress, because they were monstered for being unnatural and mannish, and to counterbalance that they had a deliberate tactic of dressing in a conventional, ladylike way. There’s a sense of power coming from embodying your gender, not denying it.’

Practical or mundane garments such as floor length aprons were also emblazoned with slogans and declarations of allegiance to the fight for the right to vote. However, these domestic, embellished items brought scorn and abuse upon the defiant women who wore them to go about day-to-day duties within and beyond the home. Wearing accessories in suffragette colours was not confined only to women, and men who supported the fight for women to have the right to vote ported the purple, green and white as ties, scarves, or hatbands.

The women who led the suffragette movement tended to be from the middle and upper classes. It is acknowledged that they were the women who could afford to take the time and bear the financial costs that were necessary to campaign and drive The Cause. Although cotton mill workers from Pankhurst’s native Manchester could not spare the time to march, and indeed fell away from the movement after Emmeline’s departure for London, she and her (militant) daughter Christobel still marched for all women’s right to vote.

What is sometimes forgotten is that during the Great War, suffragettes suspended activism and instead directed their energies to supporting the Country. They were encouraged by the movement’s leading members to volunteer for essential work such as in munitions factories and transport. For this contribution they earned the belief of government that women could be given responsibility, and could possibly make an informed decision.

So, at the end of World War 1 in 1918, ‘respectable’ ladies over 30 years old who were householders, or married to householders, were given the vote. 10 years later, in 1928, The Representation of The People Actmade women’s voting rights equal with men. The Suffragettes, their forebears, the Suffragists and the Blue Stocking before them (see Selvedge Issue 28) have enabled women today to have a voice and the right to place an X in a box on voting day.

Guest edited by Nicola Donovan

Nicola Donovan pins down the subversive style of the Suffragettes: Soldiers in Petticoats was first published in Selvedge issue 67, Migration.