A Suffragette Detective Story

This guest article was written by Denise Jones who wrote her doctoral thesis about suffragette embroideries worked in Holloway Prison last year and has an exhibition of her textile practice as research at The Lightbox Art Gallery, Woking 8th - 20th June, 2021.

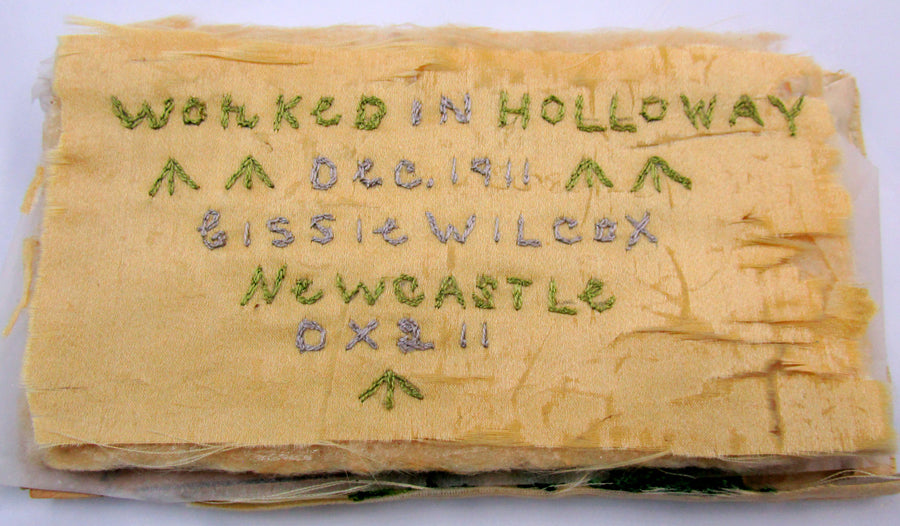

Image: Fig.1 Cissie Wilcox, an embroidered panel (December, 1911). All images © Museum of London.

Image: Fig.1 Cissie Wilcox, an embroidered panel (December, 1911). All images © Museum of London.

I am in a backroom at the Museum of London looking at some of the embroideries. I’ve already seen some of them online and two embroideries worked by Cissie Wilcox have caught my attention.

They are on the table in front of me: a small fraying fragment of silk cloth embroidered with Newcastle, DX 2.11, broad arrows and December 1911 and an embroidered plain handkerchief with the names of fifteen suffragettes, dated January 28th 1912. Both of the embroideries are worked in chain stitch in purple and green threads – two of the colours of the militant Women’s Social Political Union (WSPU) led by Mrs Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel. They were both worked in Holloway Prison and it is likely that they were embroidered during ‘associated labour’, where the women sewed or knitted clothes for prisoners. The embroidery threads and cloth were probably smuggled into prison.

Fig. 2 Cissie Wilcox, an embroidered handkerchief (January, 1912).

Fig. 2 Cissie Wilcox, an embroidered handkerchief (January, 1912).

Holding the embroideries sends a tingle through my nervous system. Unlike the digital archive I can sense the physicality of the materials, their dirtiness, the scale of them and also get under the skin of the maker. I can begin to understand how she thought and how she fiddled with the cloth and thread, what decisions she made. I can look at the back of the work and understand her hand. I am touching, looking and thinking about them and about her.

Fig. 3 Cissie Wilcox, package fragments (December, 1911). Photograph: Denise Jones.

I can see that contrary to its online representation the silk fragment is part of a package and that the fragment was the backing fabric that was cut away. The package was a tube of cloth filled with padding and two pieces of cardboard taken from a box from well known fruit and vegetable retailer Shearns, in Bloomsbury. The card would have stiffened the package.

The front of the package is a hand-embroidered pink rose cut from a larger piece of work (maybe a bell pull?). The silk backing has been cut away from the package very quickly as if someone was in a hurry to retrieve something from inside it. Did Cissie Wilcox’s package conceal a letter? Was it smuggled in or out of Holloway with her washing parcel? Was the package purposefully made from embroidery to deflect the eye and conceal the contents? Who would suspect embroidery? And, who was Cissie Wilcox and why was she in prison at this time?

Fig. 4 Drawings (2015). Photograph: Denise Jones.

The handkerchief provides the first clues in that it has prison sentences and dates in three corners, and the work is dedicated to a Mrs Terrero. It was a gift from the women Cissie listed in the lower half of the handkerchief. Looking through Votes for Women and provincial newspapers I discovered that Cissie was arrested and imprisoned on the dates she recorded on the handkerchief. She was a militant member of Newcastle WSPU hence the words on the fourth corner ‘WSPU motto Deeds not words’ and ‘Newcastle’ on the fragment.

In November 1910 Wilcox was badly kicked and punched by the police for breaking windows after a suffragette deputation to Parliament. A letter written to the journal Justice in March 1911 by Manuel Terrero (the husband of Mrs Terrero) described how Cissie’s injuries were the worst of the four women who had stayed with them in the aftermath of the event (later known as ‘Black Friday’). He explained how his wife and a female doctor had examined the women. Cissie reported in Votes for Women in December 1911 that she still had an open wound six weeks later. What we can deduce from this is that Cissie knew Mr and Mrs Terrero before 1912 (the year she gave Mrs Terrero the gift of the handkerchief). Why did she embroider the handkerchief for Mrs Terrero?

Fig. 5 Janie Terrero (c. 1912). © Museum of London.

The women listed with Cissie on the handkerchief were all sentenced for window breaking in December 1911 and were in Holloway Prison over Christmas 1911 and New Year 1911-12. It must have been a terrible time for all the women and Cissie was far away from home and her family. Most of the women were eventually released on February 10th 1912 as was Cissie, and they were met with ‘gaily decorated omnibuses’, driven to a restaurant and received by Christabel Pankhurst for breakfast.

In the suffragette paper Votes for Women, December 1911, the administration staff had made a plea for items and donations for hampers for the women. The following issue of Votes for Women, 1911 named Janie Terrero, the secretary of the Pinner branch of the WSPU as a contributor. Was the handkerchief, embroidered by Cissie Wilcox, a personal gift from these women to Janie Terrero for her kindness? And how did this handkerchief end up in the Museum of London? Did Janie Terrero deposit it there in 1928 when The Suffragette Fellowship contacted her about her own experiences as a suffragette? Was Janie Terrero the mysterious recipient of a washing parcel and letter from Cissie? Did Janie send Cissie a letter or did Cissie send the letter to her? We might never know the answers to these questions. There is more to be told however, about what happened to Cissie Wilcox, a relatively unknown suffragette, after she was released from Holloway in 1912 and about Janie Terrero’s involvement in suffragette militancy.

Cissie was arrested again in 1913 for attempting to set fire to a newly built school in Whitely Bay, Northumberland. The police had been mysteriously notified beforehand about the act. Provincial newspapers described how the police were tipped off and waited for the women to set the fire. Cissie was caught and when the policeman asked her about two boxes of matches she dropped on the railway bridge she replied ‘Perhaps they are yours’. She was asked to remove her coat and the pocket contained one shilling and sixpence and a broken matchstick!

It took me three years to find Cissie Wilcox in the official records. Eventually, I found a reference to her arrest in a local newspaper where her address was reported as 9, Mafeking Street, Gateshead. Her real name was Mary Ellen Wilcox and in 1901 Cissie was recorded as being a domestic servant. In the 1939 England and Wales Register, Cissie a retired nurse was living with her sister Eva, a retired matron in Horsham, East Sussex.

And who was Janie Terrero? She was much easier to find, as she was a woman of means, educated, and she left a paper trail. She was married to Manuel Terrero who was a member of the Men’s Political Union.

They used their newly built house and garden in Pinner to host WSPU branch meetings, one of which was attended by the suffragette Lady Constance Lytton. Manuel Terrero presides in a photograph and is seated to the left (see figure 6).

Fig. 6 The Terrero’s ‘At Home’ with Lady Constance Lytton, in the garden at Rockstone House, Pinner (July, 1911). Taken from: Raeburn, A. (1976) The Suffragette View. Newton Abbott, Devon: David and Charles. p.52.

Janie was imprisoned in March 1912, for window breaking and sentenced to four months in Holloway Prison. An account of her prison experiences are recorded in a document held at the Museum of London.

She also embroidered. She worked a panel to commemorate the twenty women (including herself), who were forcibly fed in April 1912 (see figure 7).

As the spokeswoman for her wing she tried to avert the second hunger strike and the forcible feeding of the women in June 1912. She was eventually released in late June because of weakness and failing health. She was 54. After Manuel’s death in 1926 Janie returned to live in Belsize Park, Hampstead until she died in 1944. The couple are buried together in Southampton and they were childless.

Fig. 7 Janie Terrero, embroidered panel (1912). © Museum of London.

What stories these three embroideries help to recall. They are portals into the lives of these two women, let alone the stories of the other long forgotten women listed on Cissie’s handkerchief and Janie’s panel. The embroideries materially connect us to the women. We know that over a hundred years ago they handled the same cloth and thread and thought just like we do about how to make chain stitch or sew a seam. They also probably put thread to their lips to thread the needle, even pricked a finger, leaving their DNA embedded in the cloth. When we unpick their stories we simultaneously touch and are touched by them and we are also reminded about what we do when we embroider through cloth.

Written and researched by Denise Jones.

Find out more about the accompanying exhibition, Textures of Understanding, on The Lightbox Art Gallery website.